For many people Cambodia’s history is synonymous with Angkor Wat and the Khmer Rouge, but the Kingdom of Wonder has another, upbeat story to tell (albeit with a tragic ending). The era known as Cambodia’s Golden Age of Music is still very much a part of the country’s popular culture.

Rock royalty: Surviving records by Sin Sisamouth and Ros Sereysothea. Image courtesy CVMA.

In the 1960s Phnom Penh was one groovy city. The city was a cultural hotspot with its own, distinctive style of modernist architecture; an international playground for an affluent, arty crowd who flocked to its many cinemas and danced at fashionable nightclubs to music from the country’s top recording artists like Sin Sisamouth, Ros Sereysothea, and Pan Ron.

This Golden Age began in 1955 when Norodom Sihanouk — these days revered as the King Father — gave up the throne to become the country’s first democratic head of state and set about an extensive program of modernization. It lasted fifteen years until Sihanouk, himself a film-maker, musician, and composer, was ousted in a coup that opened the way to the rise of the Khmer Rouge and the genocide that followed.

The music that defines the era — and lives on today in hearts and minds; wedding marquees; karaoke parties; outdoor exercise classes; and the occasional, loitering tuk tuk — was a glorious hybrid of western and Khmer. All searing, psychedelic guitars and soaring keyboards, frequently underpinned by Latin rhythms, and crowned with ethereal, high pitched, female vocals. The country’s music industry flourished.

Demand for these idiosyncratic sounds was so high in 1960s Cambodia that many hundreds of recordings were made and pressed onto vinyl for a growing number of record labels, a great many featuring the man sometimes called Cambodia’s Elvis, Sin Sisamouth, who was also a prolific composer. He and Ros Sereysothea, a.k.a. the Golden Voice, were friends and frequent collaborators. The two met while recording for Royal Cambodian Radio, the station that created the stars of the day.

If some of the old songs sound teasingly familiar, it’s no wonder. Cambodian artists borrowed freely from the tunes they heard on western pop records. As for the lyrics, they simply composed new ones in their own language that their audience would relate to, typically tales of love, loss, and betrayal.

The most usual paths to fame, for female singers in particular, were via the many singing contests held across the country or as members of the musical troupes that belonged to various ministries and state-owned companies like the Société Khmère des Distilleries , which spawned the singing careers of famous sisters Sieng Vanthy and Sieng Dy.

Pan Ron was particularly popular with the young set in Cambodia. Image courtesy CVMA.

Pan Ron (also called Pen Ran) was the singer most admired by younger fans for her modern approach; she liked to dance when she sang and her songs, I’m unsatisfied and Chills to My Spine among them, were a little more suggestive than those of her contemporaries.

Probably the country’s least conforming artist was rocker Yol Aularong, whose self-penned songs like Cyclo were irreverent and drily humorous. Possibly the most evocative depiction of the era (very little archive material escaped Khmer Rouge destruction), its music and fashions is found in Norodom Sihanouk’s film La Joie de Vivre , which features cameos by some of the leading artists of the time — and some very far-out dancing.

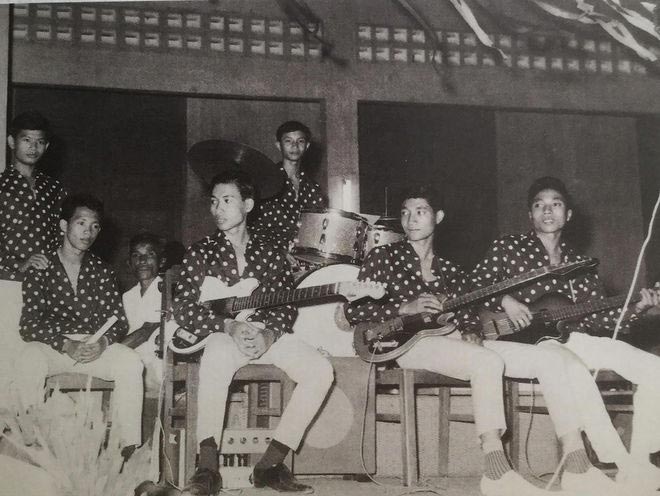

Guitar heroes Baksey Cham Krong. Image courtesy Mol Kagnol.

Acclaimed as Cambodia’s first guitar band, Baksey Cham Krong was formed in the mid-1950s by brothers from the affluent Mol family. As guitars were hard to come by, at any price, they started out by assembling their own. The bands that followed on their heels included Apsara , the Bayon Band, and Drakkar. By the time the latter released its first album, on cassette, the decade had turned. Drakkar never got to reap the success of its best selling record — happily since re-mastered from a salvaged copy and re-released — the Golden Age was over and Khmer Rouge troops were closing in on Phnom Penh.

Tragically, few of the singers and musicians survived the genocide years, including Sisamouth, Sereysothea, Aularong, and Pan Ron. Little is known for certain about how they met their deaths. The records they made were also mostly lost, though enough were saved for the songs to eventually resurface in the late 1980s on roughly-copied cassettes and to subsequently find their way onto western-made compilation CDs. What is left of the original vinyl is rare and highly collectable.

The music, meanwhile, has acquired a growing international fan base aided by bands like the USA’s Dengue Fever and Phnom Penh-based Cambodian Space Project, the latter now sadly defunct following the tragic death of singer, Kak Chantthy, in a traffic accident in 2018.

Miss Sarawan reviving the Cambodia’s Golden Age.

The music lives on….

On stage: Phnom Penh-based Khmer/western collaboration Miss Sarawan and Khmer/French duo Arome Khmer play live at venues around town. Catch a rousing revival of Khmer rock and roll by the talented musicians and singers who sometimes perform together under the banner The Blind Musicians of Cambodia at Boran House on Street 310.

Online: Cambodian Vintage Music Archive

On record: Two highly recommended compilation album series to seek out are Groove Club Volumes 1 to 4 (Lion Productions) and Cambodia Rocks Volumes 1 to 4 (Khmer Rocks).

On Film: Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten (Director John Pirozzi) — periodic screenings at venues like Bophana Centre and Meta House.

On the shelf: Space Four Zero, the Phnom Penh gallery and music and collectibles store specializes in Golden Age music.

On the page: Susan Haythorpe’s book, Lost Generation: The Story of Cambodian Rock and Roll, is available from online bookstores and in Cambodia at branches of Monument Books and Space Four Zero.

Leave a Reply