In this series, an offshoot of our Expat Q&As, we talk to expats that have been living in Cambodia for years and years. Long-term expats have the best stories to tell, and this week’s expat, British national Jenny Pearson, is no exception.

Jenny Pearson has been living in Cambodia since 1995, so long, in fact, that she holds Cambodian citizenship. She arrived as a VSO volunteer and went on to found VBNK, Cambodia’s leading capacity-building organization (she’s also written several books that we’ll be reviewing here on the blog soon). We talked to Jenny about what life was like for an expat in Cambodia in the 90s, and what it’s like now.

19 years in Cambodia and counting.

What was Cambodia like when you first arrived and how has it changed?

I arrived in Cambodia in January 1995 as a VSO volunteer on a two year placement. At that time I classified myself as a refugee from the English public sector–I really wasn’t enjoying what I did any more, hated the increasing levels of bureaucracy in my work, and had decided that I needed some time out to think about what I wanted to do with the rest of my life. Cambodia made that decision for me, as I realised very soon after arriving that I didn’t want to go back to what I had left, and within a year I was seriously planning what to do here after my VSO placement ended.

So much has changed in Cambodia since the mid-90s it’s hard now to remember a lot of details of what it was like. It was a country still in the throes of civil war, and we VSOs were subject to quite a few restrictions to do with our security so I didn’t get out of Phnom Penh much. That was apart from the very limited transport options and hellish roads–you could only go to Sihanoukville in a convey that had radio contact and the only way to get to Siem Reap was to fly–which was expensive for anyone on a volunteer allowance.

Both of those places have changed almost beyond recognition with the developments of recent years, and I’m not sure I think it’s all for the better. For sure it could be very scary back then, the tensions between the different factions in the coalition government were at times palpable here in Phnom Penh. Outside the city there were armed soldiers at ‘roadblocks’ every few kilometres on rural roads, disbursing a few riel would secure your passage through. Everyone locked themselves into their houses by the time the light faded at the end of the afternoon. I was robbed at gunpoint on Street 63 in broad daylight at 2.30 in the afternoon, but mostly we expats escaped the worst of the crime.

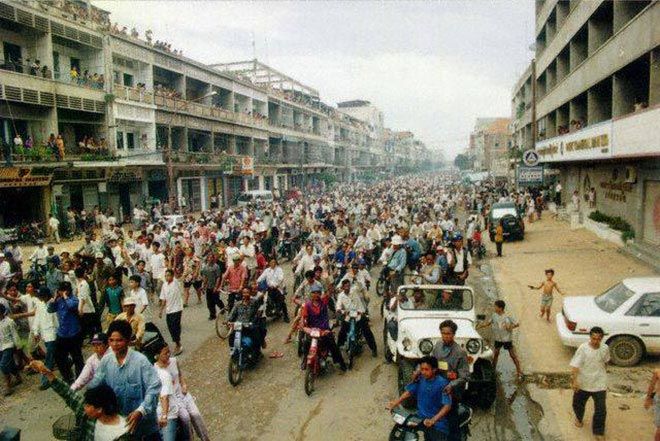

Anti government protests in Phnom Penh, 1998. Photo via Amazing Cambodia.

What you could get in the supermarkets was extremely limited compared to now, and like now things would be there one day and not seen again for the next six months, only then it was much more basic. The thing I missed most was that there was no cheese, only the processed triangles, so the selections now seem wonderful by comparison. The same with restaurants, we are spoilt for choice now.

Even in the middle of the city the roads were terrible and there were only one or two sets of traffic lights in the city and they didn’t work very often, maybe once a week, but the traffic was minimal compared to now. The only people who had big cars with the UN, embassies and NGOs, everyone else was in little old white Toyota Camrys. Streets in Boeung Keng Kang still had pigs and chickens wandering around. There were a lot of very beautiful wooden houses, each sitting in the middle of a plot surrounded by trees, so the streets had a very different feel back then.

But things started to change fairly quickly. The roads got fixed up bit by bit. Wooden houses went and the Thai style villas started to appear in their place, now its the apartment blocks. Areas of the city have changed dramatically with the advent of the garment factory and influx of people from the country wanting to work in them. Outside of Phnom Penh there are some changes, especially in towns and areas where the roads have been done, but fundamentally there is little change to rural life and the poverty that many in rural areas experience.

What is your life in Cambodia like now?

In 1999 I made the decision to live outside Phnom Penh in a village near Takhmau. It isn’t a rural village, more a place that in England we would call a dormitory for the city. At that time my friends thought I was mad, and assumed that I was just going to use it as a weekend or holiday place. It’s 11 km from my house to the Monument but everyone worried about how I would cope with the commuting. After the hour and half each way I used to do every day in London, this is a piece of cake! Now they look wistfully at my lovely house in a quiet place, surrounded by trees, with no pollution, traffic noise or building going on all around me and recognise that I have a really great quality of life compared to theirs in the city.

Across from the main post office, Phnom Penh.

I was fortunate to get connected with a Cambodian family when I first arrived and we continue living together – I look after them and they look after me. Most days it works very well, though there are still some when we have cultural misunderstandings. In particular ideas about the best way to raise children are very different between English and Cambodian cultures, so that creates some tensions at times. But on the whole I feel very lucky – living with a Cambodian family in a beautiful home gives me many experiences and insights that I think others don’t have access to.

What have you learned during your time in Cambodia?

It’s impossible to say what I have learned from Cambodia. I came full of big ideas about how I was going to help in my two-year volunteer placement, and of course soon started to tune into the realities and challenges of rebuilding a country so profoundly damaged as Cambodia had been. I saw that while I had something to offer, I needed to seriously reframe how I offered it and any expectations I might have about the change that would follow. I long since came to realise that Cambodia has taught me much more than I have been able to give in return.

Among many important lessons some that stand out are that we in the West have lost many valuable things in our society including the strength of the extended family, respect for elders, practical skills and how to value them. There have been many days when things that Cambodians have said and done have frustrated, challenged or puzzled me, and despite my years here there is still a great deal I don’t understand about this culture. But what I have come to respect enormously is Cambodian resilience. That any society, or individual within it, can have gone through the loss and devastation that Cambodia experienced during decades of war and turmoil and come through it with dignity and a smile on their face is a great lesson to us all. I’m not sure I would have had the strength to do it and that has been my biggest learning of all.

Jenny Pearson is the author of several wonderful books about working in Cambodia. Creative Capacity Development is available on Amazon and at Monument Books in Cambodia. The rest of her publications are available through VBNK.

Very interesting and insightful piece, Jenny must have seen some great changes. I hope she continues to enjoy life there.

Just starting to learn about Cambodia

A nice, thoughtful perspective. Jenny is both brave and smart.

I remember Jenny. I was also a VSO volunteer from 1996-1998, based in Koh Kong.